The Secret Death

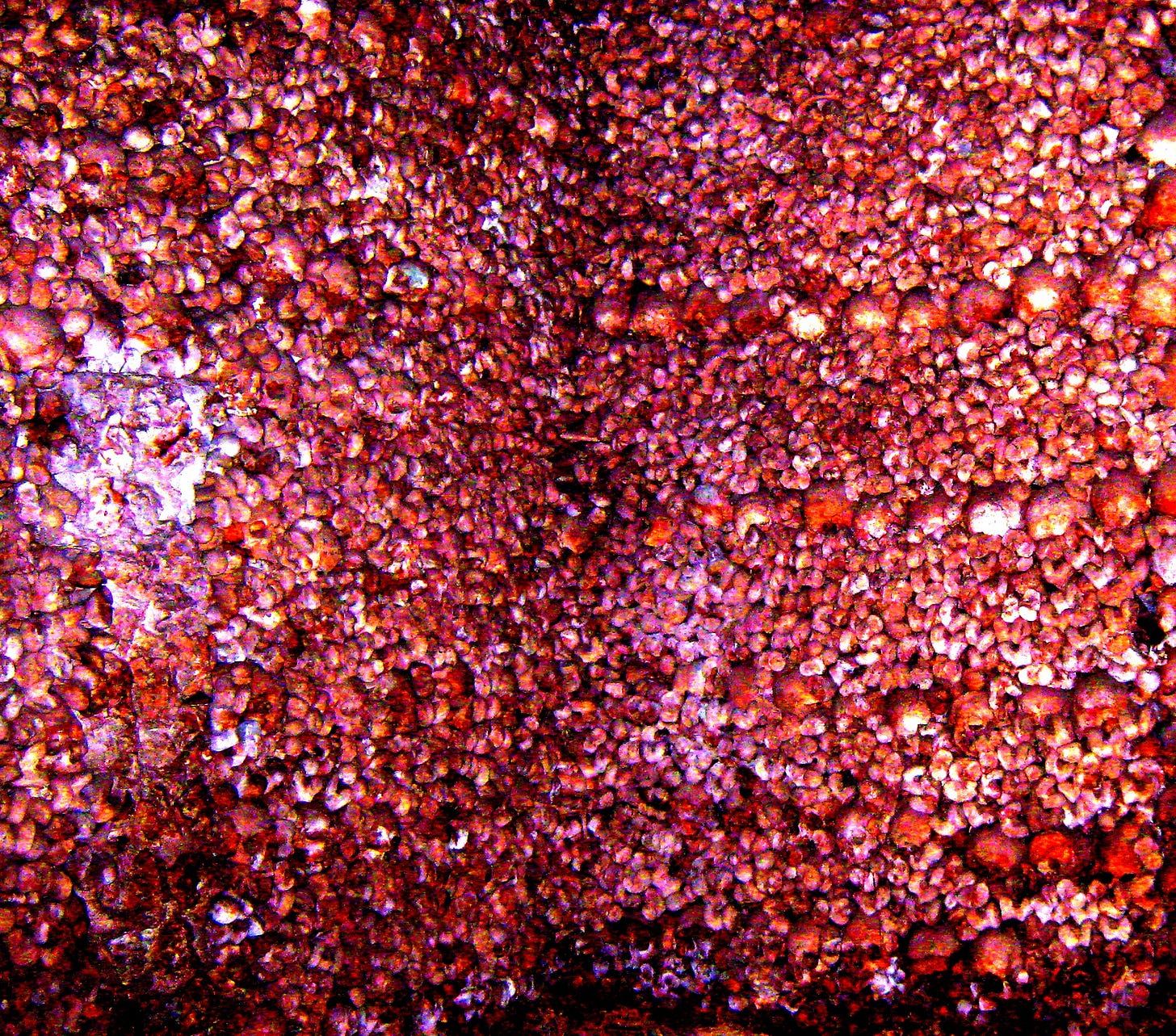

[A wall on the Chapel of Bones in Evora, Portugal—yes, those are human bones]

Any death that announces itself in advance is inevitably a more horrible death, at least for the one who dies, than the one that comes of a sudden and discretely removes you, quickly, easily, with no time for the anguish and the preparation for a thing for which one can never, …