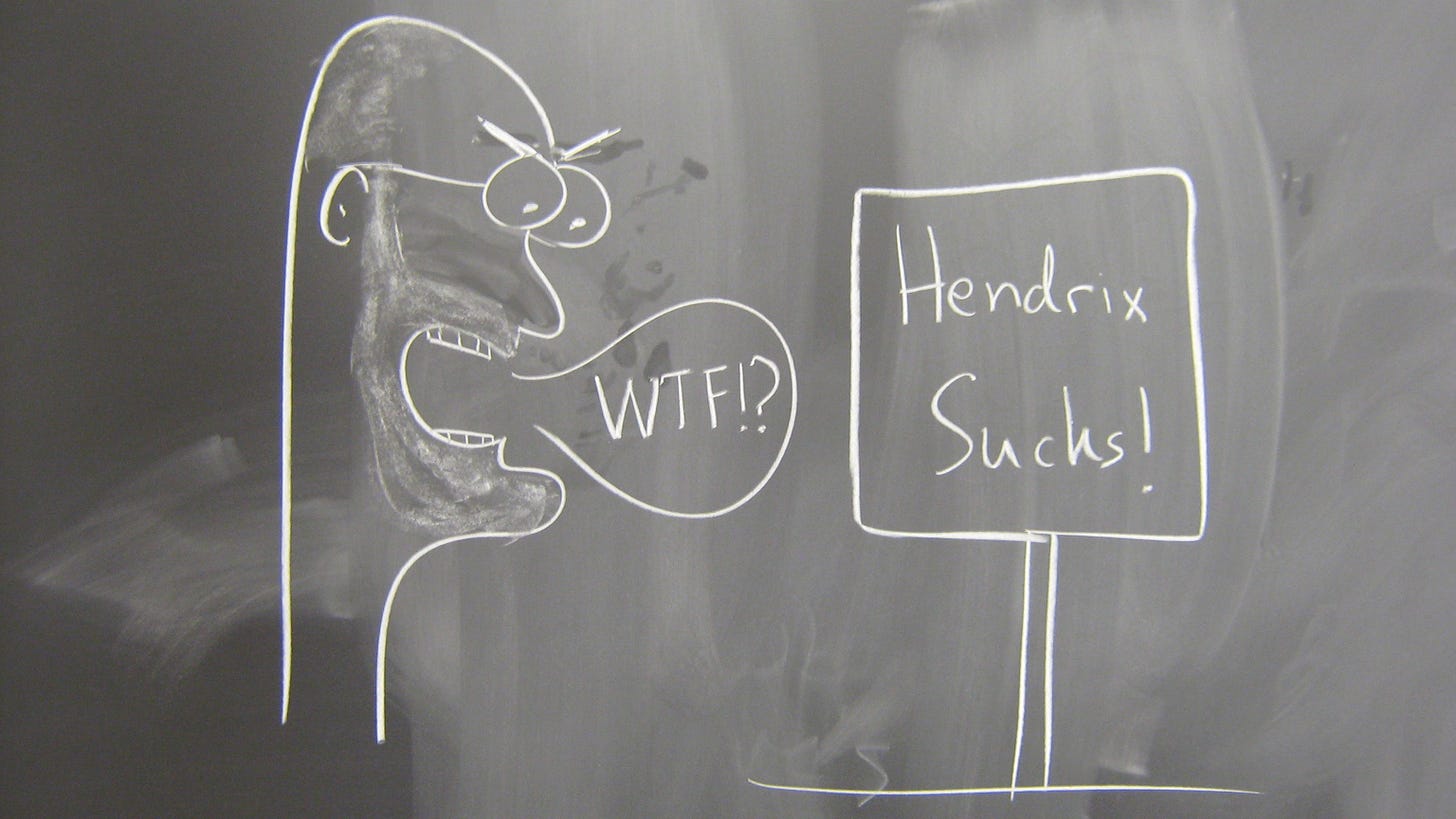

[Student art left on the chalkboard in a course in which it became clear to them how I feel about Mr. Hendrix]

Just a few thoughts on this guy, who remains for me, more than 40 years since I first heard him, one of the transcendent figures in rock music.

He’s become, I fear, something of a cliché for some, especially for younger people who’ve never prop…