A Waltz for Evelyn Hinrichsen in Oregon

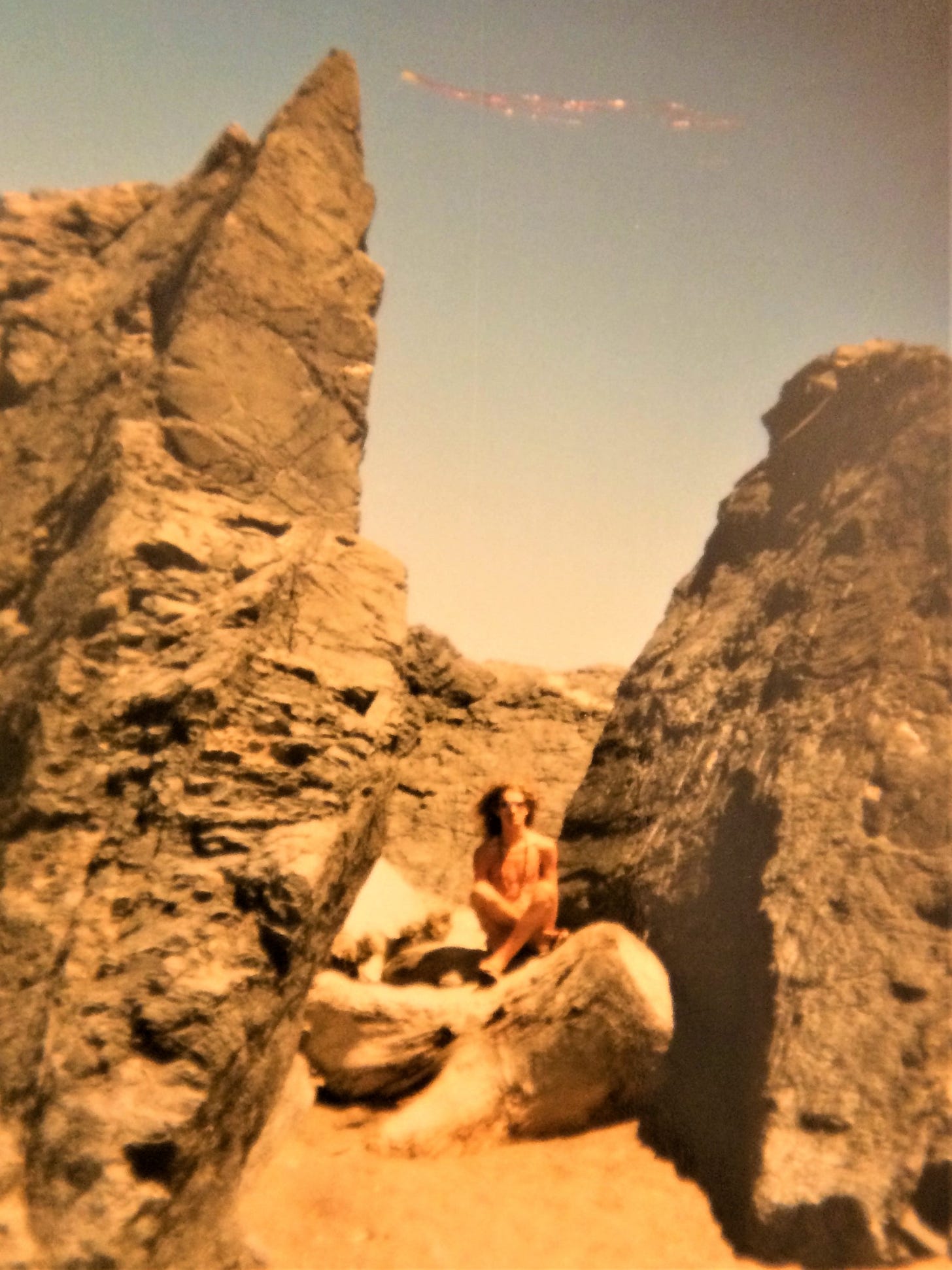

[Somewhere in the Nevada desert, right around the time described herein]

Just out of college, I lived in a rented room on the second floor of a home in a little town in the mountains of a Western state 2700 miles from the one in which I grew up.

A nice elderly lady owned the place. She didn’t ask me anything when I came to inquire about it, and she wasn…