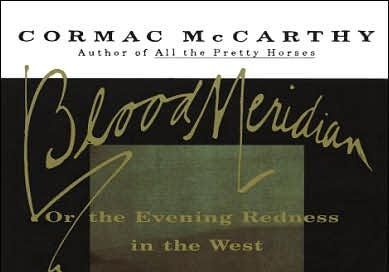

A brief ride through the evening redness in the West

Some further notes on _Blood Meridian_, having just finished it with my Faces of Death class

We just finished reading the book this week. The third time, I believe, that I’ve used it in this course.

It is a tough book for students.

Why then do I give them this book, which even Harold Bloom, one of its biggest academic fans, admits he had trouble with in the early going because of the ubiquitous, meticulously described acts of violence and murde…